There is almost too much to say about these three films. In fact, only one film in the trilogy actually made it onto the IMDB Top 250 list, that being the final film, Red. Although these are each excellent as stand-alone works, they are best when seen as a whole. For that reason, I am going to review each of them separately. For the unfamiliar, Polish director Krzysztof Kieslowski’s last work, “Three Colors Trilogy” takes its name from the colors of the French flag and its themes from the ideals represented by those colors: blue (liberty), white (equality), and red (friendship).

There is almost too much to say about these three films. In fact, only one film in the trilogy actually made it onto the IMDB Top 250 list, that being the final film, Red. Although these are each excellent as stand-alone works, they are best when seen as a whole. For that reason, I am going to review each of them separately. For the unfamiliar, Polish director Krzysztof Kieslowski’s last work, “Three Colors Trilogy” takes its name from the colors of the French flag and its themes from the ideals represented by those colors: blue (liberty), white (equality), and red (friendship).

White is the second film in Kieslowski’s Trilogy, and it deals with the idea of equality. In my opinion, it may not be the strongest “film” of the three, but it is the one that I enjoyed the most. It maintains a balancing act between comedy and tragedy. The tone and feel of White was different, almost to the point of feeling out of sync, from the entire trilogy. The lead character is male unlike the other two films, even though Julie Delphy technically gets top billing, she only appears in about 15-20 minutes of the film. Polish actor, Zbigniew Zamachowski (Now you know why Delphy’s name was on all the promotional material!), puts in a powerful performance that goes from comedic pantomime to heartbreaking despair. Finally, White is told in a very plain way when you consider the imagery of Blue or the wonder of Red. White is simply less artsy, which is probably why I enjoyed it so much. Sometimes, forcing myself to sit through artsy films is like making my kids eat their vegetables, they don’t really want to do it, but they are good for them. I think most moviegoers could use a good dose of eating their cinematic vegetables and cut back on some of the “junk food,” but that is a post for another day.

White is the second film in Kieslowski’s Trilogy, and it deals with the idea of equality. In my opinion, it may not be the strongest “film” of the three, but it is the one that I enjoyed the most. It maintains a balancing act between comedy and tragedy. The tone and feel of White was different, almost to the point of feeling out of sync, from the entire trilogy. The lead character is male unlike the other two films, even though Julie Delphy technically gets top billing, she only appears in about 15-20 minutes of the film. Polish actor, Zbigniew Zamachowski (Now you know why Delphy’s name was on all the promotional material!), puts in a powerful performance that goes from comedic pantomime to heartbreaking despair. Finally, White is told in a very plain way when you consider the imagery of Blue or the wonder of Red. White is simply less artsy, which is probably why I enjoyed it so much. Sometimes, forcing myself to sit through artsy films is like making my kids eat their vegetables, they don’t really want to do it, but they are good for them. I think most moviegoers could use a good dose of eating their cinematic vegetables and cut back on some of the “junk food,” but that is a post for another day.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tc8RZ7QgWZA]

White follows the journey of a very misfortunate Polish hairdresser named Karol Karol. I have to wonder if Kieslowski didn’t make this film as an ode to the great Charlie Chaplin because Karol means “Charlie” in Polish. We see Karol approaching a courthouse in Paris, as he looks up seemingly hopefully at a bird flying in the air, his hopes come crashing down as the bird uses him as a toilet. This brief scene sets the tone for the rest of the film in which we will see Karol being used and abused repeatedly. He is at the courthouse because his wife, Dominique, who is a Paris native, wants to divorce him because the marriage has never been consummated. He is impotent.  He is forced, in the courtroom, to use a translator because his French is weak, this only adds to the feeling of his impotence, he can barely even stand up for himself. She testifies that she no longer loves him, and he pleads with her to come back to Poland with him. But after we see Juliette Binoche poke her head in the courtroom (a tie-in from Blue). The divorce is granted, and Karol is on the streets with all his possessions in a big suitcase. His bank account is frozen and Karol can do nothing but watch as a bank employee cuts up his card. And as if that weren’t enough, she also frames him for arson. Unfortunately, there is no background given to Dominique’s character to reveal why she has such hatred for Karol. We see images of her smiling face at their wedding, but besides that, she is merely painted as an evil character.

He is forced, in the courtroom, to use a translator because his French is weak, this only adds to the feeling of his impotence, he can barely even stand up for himself. She testifies that she no longer loves him, and he pleads with her to come back to Poland with him. But after we see Juliette Binoche poke her head in the courtroom (a tie-in from Blue). The divorce is granted, and Karol is on the streets with all his possessions in a big suitcase. His bank account is frozen and Karol can do nothing but watch as a bank employee cuts up his card. And as if that weren’t enough, she also frames him for arson. Unfortunately, there is no background given to Dominique’s character to reveal why she has such hatred for Karol. We see images of her smiling face at their wedding, but besides that, she is merely painted as an evil character.

Now homeless and penniless, he takes to playing “music” on a comb in the train station in hopes for a handout. While playing a Polish folk song, he catches the ear of one of his countrymen named Mikolaj. They strike up a conversation about how he got in that situation and Mikolaj offers to pay his way back to Poland, but he cannot leave the country in such a public way because the authorities are still looking for him. So they come up with the plan that he should stow away in the suitcase, and leave behind the alienation and isolation of France. This seems like a strange way for a French financed movie, in a series about the French national colors, on the topic of equality to begin. I wonder if Kieslowski didn’t harbor some feeling of alienation against his adopted country, himself being Polish like the lead character. Mikolaj agrees to this plan and hopes that his new friend can survive the four-hour flight crammed inside a suitcase with a few personal belongings and a stolen bust that reminds him of Dominique, who he still loves.

Now homeless and penniless, he takes to playing “music” on a comb in the train station in hopes for a handout. While playing a Polish folk song, he catches the ear of one of his countrymen named Mikolaj. They strike up a conversation about how he got in that situation and Mikolaj offers to pay his way back to Poland, but he cannot leave the country in such a public way because the authorities are still looking for him. So they come up with the plan that he should stow away in the suitcase, and leave behind the alienation and isolation of France. This seems like a strange way for a French financed movie, in a series about the French national colors, on the topic of equality to begin. I wonder if Kieslowski didn’t harbor some feeling of alienation against his adopted country, himself being Polish like the lead character. Mikolaj agrees to this plan and hopes that his new friend can survive the four-hour flight crammed inside a suitcase with a few personal belongings and a stolen bust that reminds him of Dominique, who he still loves.

However, once the plane lands in Warsaw, in an unsurprising but hilarious twist, Mikolaj learns that the luggage has gone missing. We then catch up to Karol in a garbage dump outside Warsaw, where some luggage thieves have inadvertently taken him, probably thinking the weight of the bag was a good indicator of the value of its contents. Of course, they try to rob him, but besides the stolen bust (which they break) and two francs which he fights for, he has nothing for them to steal. Perhaps out of pity, they beat him, but do not kill him, and then leave him lying in the snow. Karol struggles to lift his now bloodied face and looks out to see the white snow swept garbage dump and says, “home at last!”

However, once the plane lands in Warsaw, in an unsurprising but hilarious twist, Mikolaj learns that the luggage has gone missing. We then catch up to Karol in a garbage dump outside Warsaw, where some luggage thieves have inadvertently taken him, probably thinking the weight of the bag was a good indicator of the value of its contents. Of course, they try to rob him, but besides the stolen bust (which they break) and two francs which he fights for, he has nothing for them to steal. Perhaps out of pity, they beat him, but do not kill him, and then leave him lying in the snow. Karol struggles to lift his now bloodied face and looks out to see the white snow swept garbage dump and says, “home at last!”

After staying with his brother and working at the family hairdressing salon at which he is extremely popular. Karol decides that if he can’t get Dominique back, then the very least he can do is balance the scales and get back at her. Using his ingenuity and taking advantage of the new free market economy of post-communist Poland, Karol amasses a fortune.  Then with the help of Mikolaj and a trusted employee of his new company, Karol fakes his own death and leaves his fortune to Dominique. When she comes to Warsaw for the funeral, he sneaks into her hotel room and, after the initial shock, they make love, finally consummating their relationship. However, in the morning, Dominique awakes to the police at her hotel room door, but Karol is gone and despite her pleading in French that he is alive, Dominique is arrested for Karol’s murder. At the end, we see Dominique signing to Karol through the window of the prison in which she is being held. She tells him that she still loves him and is willing to marry him again, if she can get out of prison. Karol begins to cry. He has succeeded in achieving equality with his ex-wife, but it is a bittersweet victory. This film is not uplifting like Blue or Red it is a dark comedic tragedy.

Then with the help of Mikolaj and a trusted employee of his new company, Karol fakes his own death and leaves his fortune to Dominique. When she comes to Warsaw for the funeral, he sneaks into her hotel room and, after the initial shock, they make love, finally consummating their relationship. However, in the morning, Dominique awakes to the police at her hotel room door, but Karol is gone and despite her pleading in French that he is alive, Dominique is arrested for Karol’s murder. At the end, we see Dominique signing to Karol through the window of the prison in which she is being held. She tells him that she still loves him and is willing to marry him again, if she can get out of prison. Karol begins to cry. He has succeeded in achieving equality with his ex-wife, but it is a bittersweet victory. This film is not uplifting like Blue or Red it is a dark comedic tragedy.

The idea of resurrection is a strong theme in this film. Karol metaphorically dies in order to leave Paris, throwing away all his diplomas in the train station, and being buried in the suitcase, and he arises in his homeland and begins his life over again as a businessman. In Machiavellian fashion, Karol fakes his own death as a bid to lure Dominique to Warsaw to exact his revenge. Mikolaj is also resurrected. Being suicidal, he pays Karol to shoot him, but since he is his friend, he loads the gun with a blank. After pretending to kill him, Karol warns him, “The next one is real.” Karol gave Mikolaj some perspective and a new lease on life.

If you remember in Blue, Julie is so absorbed in her own emotions that she doesn’t even notice the old woman and the recycling bin. But she also shows up in White while Karol is shivering on the streets of Paris. Karol notices her but only grins as she tries to put her bottle in the bin. I tend to think that Karol is happy to see someone to whom he finally feels equal. Finally, this is the odd man out of Kieslowski’s trilogy, because it is less artsy and more straight-forward it makes a good introductory film to get into Kieslowski’s work. But even though the ending seems like a hopeless tragedy, the true ending of White is actually revealed at the end of Red, where we see Karol and Dominique have reconciled and are re-married.

If you remember in Blue, Julie is so absorbed in her own emotions that she doesn’t even notice the old woman and the recycling bin. But she also shows up in White while Karol is shivering on the streets of Paris. Karol notices her but only grins as she tries to put her bottle in the bin. I tend to think that Karol is happy to see someone to whom he finally feels equal. Finally, this is the odd man out of Kieslowski’s trilogy, because it is less artsy and more straight-forward it makes a good introductory film to get into Kieslowski’s work. But even though the ending seems like a hopeless tragedy, the true ending of White is actually revealed at the end of Red, where we see Karol and Dominique have reconciled and are re-married.

A few isolated incidents of priests (or pastors) falling into sin is unavoidable. However, the story that Spotlight tells goes deeper to reveal the ugly truth that the Catholic Church as an institution collaborated to cover-up these incidents, protect the offenders from justice, and create an environment where further atrocities could take place. This pains me as a believer knowing that we are all fallen and corrupt people in need of grace, but I can only imagine the collective effect that these scandals have had on the church (Catholic and Protestant alike) as non-believers and marginal attenders have left in droves in the past decade. An

A few isolated incidents of priests (or pastors) falling into sin is unavoidable. However, the story that Spotlight tells goes deeper to reveal the ugly truth that the Catholic Church as an institution collaborated to cover-up these incidents, protect the offenders from justice, and create an environment where further atrocities could take place. This pains me as a believer knowing that we are all fallen and corrupt people in need of grace, but I can only imagine the collective effect that these scandals have had on the church (Catholic and Protestant alike) as non-believers and marginal attenders have left in droves in the past decade. An  Oddly enough, reporters have perhaps lost just as much respect as priests but for a completely different reason. I mean, how much more respect can you get than being the job that Superman choose to do as his alter ego. But I miss the day when news was actually news. Why does anyone care that Kim Kardashian and Amber Rose are having a feud over a couple of selfies and social media posts? Why was Tom Brady sentencing and appeal over “Deflategate” headline news while Greece’s economy was tanking and Turkey was stepping up to fight Daesh. This film reminded me that journalists used to investigate and break real stories. I hope that the pendulum swings back to the American people valuing the reporters that tell real stories that impact the community and not which celebrities just broke up.

Oddly enough, reporters have perhaps lost just as much respect as priests but for a completely different reason. I mean, how much more respect can you get than being the job that Superman choose to do as his alter ego. But I miss the day when news was actually news. Why does anyone care that Kim Kardashian and Amber Rose are having a feud over a couple of selfies and social media posts? Why was Tom Brady sentencing and appeal over “Deflategate” headline news while Greece’s economy was tanking and Turkey was stepping up to fight Daesh. This film reminded me that journalists used to investigate and break real stories. I hope that the pendulum swings back to the American people valuing the reporters that tell real stories that impact the community and not which celebrities just broke up. Channeling great films like All The President’s Men and Network, Spotlight, written by Tom McCarthy and Josh Singer, honors the account of events with their writing but never loses sight of the story they are telling. The writing is outstanding. They don’t have any agenda in this film except telling the story. I was afraid that as this subject was handled in film we would see a vilifying of the Catholic Church. On the flip side, it was also good that they didn’t try to make heroes out of the Boston Globe. It felt like they tried to be completely unbiased while writing the story. It could have been very easy for this film turn into a Lifetime or ABC Family movie and be a manipulative mess, but instead it became a polished and well-wrought film.

Channeling great films like All The President’s Men and Network, Spotlight, written by Tom McCarthy and Josh Singer, honors the account of events with their writing but never loses sight of the story they are telling. The writing is outstanding. They don’t have any agenda in this film except telling the story. I was afraid that as this subject was handled in film we would see a vilifying of the Catholic Church. On the flip side, it was also good that they didn’t try to make heroes out of the Boston Globe. It felt like they tried to be completely unbiased while writing the story. It could have been very easy for this film turn into a Lifetime or ABC Family movie and be a manipulative mess, but instead it became a polished and well-wrought film. McCarthy, also the director, lets his actors and the shocking truth take center stage. Mark Ruffalo gives a fantastic performance as a highly driven investigative journalist and has really been knocking them out of the park lately. Michael Keaton also gives another awards season-worthy performance as the leader of the Spotlight team. Stanley Tucci was amazing, though I don’t think Tucci is capable of giving a bad performance. Also, Liev Schreiber gives one of the best performances of his career. His turn as Marty Baron was calm and understated, but he takes charge in every scene he’s in, which is saying something considering the caliber of the other actors and actresses with whom Schreiber shares the screen.

McCarthy, also the director, lets his actors and the shocking truth take center stage. Mark Ruffalo gives a fantastic performance as a highly driven investigative journalist and has really been knocking them out of the park lately. Michael Keaton also gives another awards season-worthy performance as the leader of the Spotlight team. Stanley Tucci was amazing, though I don’t think Tucci is capable of giving a bad performance. Also, Liev Schreiber gives one of the best performances of his career. His turn as Marty Baron was calm and understated, but he takes charge in every scene he’s in, which is saying something considering the caliber of the other actors and actresses with whom Schreiber shares the screen.

Gittes suspects that Hollis was murdered and launches his own investigation. This eventually leads Jake to Hollis’s former business partner, Noah Cross (John Huston). Noah also happens to be the father of Evelyn and he offers double Gittes’ fee if Gittes will track down Hollis’s younger girlfriend. As his investigation continues, Gittes discovers that Hollis’ murder was connected to both the continued growth of Los Angeles as a city and a truly unspeakable act that occurred several years in the past. Nobody, it turns out, is what he or she originally appears to be. I really can’t say anything more without spoiling the film for those who haven’t seen it before.

Gittes suspects that Hollis was murdered and launches his own investigation. This eventually leads Jake to Hollis’s former business partner, Noah Cross (John Huston). Noah also happens to be the father of Evelyn and he offers double Gittes’ fee if Gittes will track down Hollis’s younger girlfriend. As his investigation continues, Gittes discovers that Hollis’ murder was connected to both the continued growth of Los Angeles as a city and a truly unspeakable act that occurred several years in the past. Nobody, it turns out, is what he or she originally appears to be. I really can’t say anything more without spoiling the film for those who haven’t seen it before.

Vertigo is a psychological thriller film directed by Alfred Hitchcock. The film stars Jimmy Stewart as a former police detective John “Scottie” Ferguson, who has been forced into early retirement due to his discovery of crippling acrophobia and vertigo. Scottie is hired as a private investigator to follow a woman, Madeleine Elster (Kim Novak) who is behaving peculiarly. The film received mixed reviews upon initial release, but has garnered acclaim since and is now often cited as one of the defining works of his career. It is currently listed at #65 on the IMDb Top 250, which I think is a travesty. It shows you what type of list the IMDb Top 250 is, to see this film and others, like Citizen Kane, outside of the top 50, but The Dark Knight currently holds the #4 place. But in the 2012 British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound critics’ poll, it replaced Citizen Kane as the best film of all time and has appeared repeatedly in best film polls by the American Film Institute.

Vertigo is a psychological thriller film directed by Alfred Hitchcock. The film stars Jimmy Stewart as a former police detective John “Scottie” Ferguson, who has been forced into early retirement due to his discovery of crippling acrophobia and vertigo. Scottie is hired as a private investigator to follow a woman, Madeleine Elster (Kim Novak) who is behaving peculiarly. The film received mixed reviews upon initial release, but has garnered acclaim since and is now often cited as one of the defining works of his career. It is currently listed at #65 on the IMDb Top 250, which I think is a travesty. It shows you what type of list the IMDb Top 250 is, to see this film and others, like Citizen Kane, outside of the top 50, but The Dark Knight currently holds the #4 place. But in the 2012 British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound critics’ poll, it replaced Citizen Kane as the best film of all time and has appeared repeatedly in best film polls by the American Film Institute.

Frank Hackett’s (Robert Duvall) character is also the future of television. He could not care less about the news division or even the quality of the network for that matter. He is a CCA (The Communication Corporation of America) man. This is the company that has purchased UBS and as far as Hackett is concerned UBS exists to serve the interests of CCA and it’s shareholders. And to that end he approves of Diana’s programming schemes once he sees the ratings skyrocket. Mind you, this film was made in 1976, years before all the cable “news” networks even existed and way before we had people willing to give up their privacy and what little dignity they have left on national television just to be recognized and become reality show “celebrities”.

Frank Hackett’s (Robert Duvall) character is also the future of television. He could not care less about the news division or even the quality of the network for that matter. He is a CCA (The Communication Corporation of America) man. This is the company that has purchased UBS and as far as Hackett is concerned UBS exists to serve the interests of CCA and it’s shareholders. And to that end he approves of Diana’s programming schemes once he sees the ratings skyrocket. Mind you, this film was made in 1976, years before all the cable “news” networks even existed and way before we had people willing to give up their privacy and what little dignity they have left on national television just to be recognized and become reality show “celebrities”. Today’s challenge was simple. If I can only recommend one movie to anyone, it is this delightful gem from Roberto Benigni. And it is a rare occasion that they have already seen it. I wonder what prevents people from seeing this film. Is it the fact that it is a foreign film or maybe that there are no recognizable movie stars in it? Perhaps it is the fact that the subject matter is generally so depressing. But the funny yet haunting Life Is Beautiful, is quite possibly the best most satisfying movie I have ever seen.

Today’s challenge was simple. If I can only recommend one movie to anyone, it is this delightful gem from Roberto Benigni. And it is a rare occasion that they have already seen it. I wonder what prevents people from seeing this film. Is it the fact that it is a foreign film or maybe that there are no recognizable movie stars in it? Perhaps it is the fact that the subject matter is generally so depressing. But the funny yet haunting Life Is Beautiful, is quite possibly the best most satisfying movie I have ever seen. Fast-forwarding a few years, Guido, now owns a small bookstore. Guido and Dora have married and have a young son. It wasn’t until writing this review that I found that his son’s name is “Joshua” spelled Giosue (Giorgio Cantarini). A Nazi presence is now creeping into their Italian town, and signs have begun to appear in shop windows: “No Dogs or Jews Allowed” Guido, who we learn is Jewish himself, jokes to a confused Giosue that he should put up a sign on their store: “No Spiders or Visigoths Allowed.” The film shifts gears when his family is arrested and sent to a concentration camp. Dora, who is not Jewish, chooses to follow her husband and child. It is at this point that Life Is Beautiful changes into a very different film. I was impressed at how seamlessly the comedy moved into the world of the death camps.

Fast-forwarding a few years, Guido, now owns a small bookstore. Guido and Dora have married and have a young son. It wasn’t until writing this review that I found that his son’s name is “Joshua” spelled Giosue (Giorgio Cantarini). A Nazi presence is now creeping into their Italian town, and signs have begun to appear in shop windows: “No Dogs or Jews Allowed” Guido, who we learn is Jewish himself, jokes to a confused Giosue that he should put up a sign on their store: “No Spiders or Visigoths Allowed.” The film shifts gears when his family is arrested and sent to a concentration camp. Dora, who is not Jewish, chooses to follow her husband and child. It is at this point that Life Is Beautiful changes into a very different film. I was impressed at how seamlessly the comedy moved into the world of the death camps. I don’t watch movies that make me sad. The reason most people watch movies is to escape for a couple of hours from your life. Who wants to escape to a sad alternate reality? On the other hand, there are plenty of movies with sad elements or scenes that make me cry no matter how many times I watch them. Yeah, that’s right I cry at movies. But that sadness is usually part of an ultimate happy ending or uplifting message.

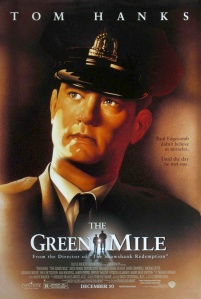

I don’t watch movies that make me sad. The reason most people watch movies is to escape for a couple of hours from your life. Who wants to escape to a sad alternate reality? On the other hand, there are plenty of movies with sad elements or scenes that make me cry no matter how many times I watch them. Yeah, that’s right I cry at movies. But that sadness is usually part of an ultimate happy ending or uplifting message. To narrow it down, I thought of 5 sad movies that I had seen. Those 5 were: My Girl, Boy with the Striped Pajamas, Dead Poets Society, A Walk To Remember, and The Green Mile. The saddest movie that I could think of was The Green Mile. At John Coffey’s execution everyone is weeping at seeing something so unjust. Everything from the scene where Paul goes into John’s cell and asks him what he wants him to do is sad. He can’t bear the thought of killing “one of God’s true miracles.” He doesn’t want to stand before God at the judgment and have to answer for why he killed an innocent man. Then as John asks to see a movie, he sits amazed at the beauty that he is beholding. At the execution I have to stop myself from sobbing out loud. Even the ending when we see Paul as an old man grieving over the loss of a friend saying that this is his punishment killing John Coffey. For those that think Stephen King is only a horror author, this film is the answer to that.

To narrow it down, I thought of 5 sad movies that I had seen. Those 5 were: My Girl, Boy with the Striped Pajamas, Dead Poets Society, A Walk To Remember, and The Green Mile. The saddest movie that I could think of was The Green Mile. At John Coffey’s execution everyone is weeping at seeing something so unjust. Everything from the scene where Paul goes into John’s cell and asks him what he wants him to do is sad. He can’t bear the thought of killing “one of God’s true miracles.” He doesn’t want to stand before God at the judgment and have to answer for why he killed an innocent man. Then as John asks to see a movie, he sits amazed at the beauty that he is beholding. At the execution I have to stop myself from sobbing out loud. Even the ending when we see Paul as an old man grieving over the loss of a friend saying that this is his punishment killing John Coffey. For those that think Stephen King is only a horror author, this film is the answer to that. There is almost too much to say about these three films. In fact, only one film in the trilogy actually made it onto the IMDB Top 250 list, that being the final film, Red. Although these are each excellent as stand-alone works, they are best when seen as a whole. For that reason, I am going to review each of them separately. For the unfamiliar, Polish director Krzysztof Kieslowski’s last work, “Three Colors Trilogy” takes its name from the colors of the French flag and its themes from the ideals represented by those colors: blue (liberty), white (equality), and red (friendship).

There is almost too much to say about these three films. In fact, only one film in the trilogy actually made it onto the IMDB Top 250 list, that being the final film, Red. Although these are each excellent as stand-alone works, they are best when seen as a whole. For that reason, I am going to review each of them separately. For the unfamiliar, Polish director Krzysztof Kieslowski’s last work, “Three Colors Trilogy” takes its name from the colors of the French flag and its themes from the ideals represented by those colors: blue (liberty), white (equality), and red (friendship). White is the second film in Kieslowski’s Trilogy, and it deals with the idea of equality. In my opinion, it may not be the strongest “film” of the three, but it is the one that I enjoyed the most. It maintains a balancing act between comedy and tragedy. The tone and feel of White was different, almost to the point of feeling out of sync, from the entire trilogy. The lead character is male unlike the other two films, even though Julie Delphy technically gets top billing, she only appears in about 15-20 minutes of the film. Polish actor, Zbigniew Zamachowski (Now you know why Delphy’s name was on all the promotional material!), puts in a powerful performance that goes from comedic pantomime to heartbreaking despair. Finally, White is told in a very plain way when you consider the imagery of Blue or the wonder of Red. White is simply less artsy, which is probably why I enjoyed it so much. Sometimes, forcing myself to sit through artsy films is like making my kids eat their vegetables, they don’t really want to do it, but they are good for them. I think most moviegoers could use a good dose of eating their cinematic vegetables and cut back on some of the “junk food,” but that is a post for another day.

White is the second film in Kieslowski’s Trilogy, and it deals with the idea of equality. In my opinion, it may not be the strongest “film” of the three, but it is the one that I enjoyed the most. It maintains a balancing act between comedy and tragedy. The tone and feel of White was different, almost to the point of feeling out of sync, from the entire trilogy. The lead character is male unlike the other two films, even though Julie Delphy technically gets top billing, she only appears in about 15-20 minutes of the film. Polish actor, Zbigniew Zamachowski (Now you know why Delphy’s name was on all the promotional material!), puts in a powerful performance that goes from comedic pantomime to heartbreaking despair. Finally, White is told in a very plain way when you consider the imagery of Blue or the wonder of Red. White is simply less artsy, which is probably why I enjoyed it so much. Sometimes, forcing myself to sit through artsy films is like making my kids eat their vegetables, they don’t really want to do it, but they are good for them. I think most moviegoers could use a good dose of eating their cinematic vegetables and cut back on some of the “junk food,” but that is a post for another day. He is forced, in the courtroom, to use a translator because his French is weak, this only adds to the feeling of his impotence, he can barely even stand up for himself. She testifies that she no longer loves him, and he pleads with her to come back to Poland with him. But after we see Juliette Binoche poke her head in the courtroom (a tie-in from Blue). The divorce is granted, and Karol is on the streets with all his possessions in a big suitcase. His bank account is frozen and Karol can do nothing but watch as a bank employee cuts up his card. And as if that weren’t enough, she also frames him for arson. Unfortunately, there is no background given to Dominique’s character to reveal why she has such hatred for Karol. We see images of her smiling face at their wedding, but besides that, she is merely painted as an evil character.

He is forced, in the courtroom, to use a translator because his French is weak, this only adds to the feeling of his impotence, he can barely even stand up for himself. She testifies that she no longer loves him, and he pleads with her to come back to Poland with him. But after we see Juliette Binoche poke her head in the courtroom (a tie-in from Blue). The divorce is granted, and Karol is on the streets with all his possessions in a big suitcase. His bank account is frozen and Karol can do nothing but watch as a bank employee cuts up his card. And as if that weren’t enough, she also frames him for arson. Unfortunately, there is no background given to Dominique’s character to reveal why she has such hatred for Karol. We see images of her smiling face at their wedding, but besides that, she is merely painted as an evil character. Now homeless and penniless, he takes to playing “music” on a comb in the train station in hopes for a handout. While playing a Polish folk song, he catches the ear of one of his countrymen named Mikolaj. They strike up a conversation about how he got in that situation and Mikolaj offers to pay his way back to Poland, but he cannot leave the country in such a public way because the authorities are still looking for him. So they come up with the plan that he should stow away in the suitcase, and leave behind the alienation and isolation of France. This seems like a strange way for a French financed movie, in a series about the French national colors, on the topic of equality to begin. I wonder if Kieslowski didn’t harbor some feeling of alienation against his adopted country, himself being Polish like the lead character. Mikolaj agrees to this plan and hopes that his new friend can survive the four-hour flight crammed inside a suitcase with a few personal belongings and a stolen bust that reminds him of Dominique, who he still loves.

Now homeless and penniless, he takes to playing “music” on a comb in the train station in hopes for a handout. While playing a Polish folk song, he catches the ear of one of his countrymen named Mikolaj. They strike up a conversation about how he got in that situation and Mikolaj offers to pay his way back to Poland, but he cannot leave the country in such a public way because the authorities are still looking for him. So they come up with the plan that he should stow away in the suitcase, and leave behind the alienation and isolation of France. This seems like a strange way for a French financed movie, in a series about the French national colors, on the topic of equality to begin. I wonder if Kieslowski didn’t harbor some feeling of alienation against his adopted country, himself being Polish like the lead character. Mikolaj agrees to this plan and hopes that his new friend can survive the four-hour flight crammed inside a suitcase with a few personal belongings and a stolen bust that reminds him of Dominique, who he still loves. However, once the plane lands in Warsaw, in an unsurprising but hilarious twist, Mikolaj learns that the luggage has gone missing. We then catch up to Karol in a garbage dump outside Warsaw, where some luggage thieves have inadvertently taken him, probably thinking the weight of the bag was a good indicator of the value of its contents. Of course, they try to rob him, but besides the stolen bust (which they break) and two francs which he fights for, he has nothing for them to steal. Perhaps out of pity, they beat him, but do not kill him, and then leave him lying in the snow. Karol struggles to lift his now bloodied face and looks out to see the white snow swept garbage dump and says, “home at last!”

However, once the plane lands in Warsaw, in an unsurprising but hilarious twist, Mikolaj learns that the luggage has gone missing. We then catch up to Karol in a garbage dump outside Warsaw, where some luggage thieves have inadvertently taken him, probably thinking the weight of the bag was a good indicator of the value of its contents. Of course, they try to rob him, but besides the stolen bust (which they break) and two francs which he fights for, he has nothing for them to steal. Perhaps out of pity, they beat him, but do not kill him, and then leave him lying in the snow. Karol struggles to lift his now bloodied face and looks out to see the white snow swept garbage dump and says, “home at last!” Then with the help of Mikolaj and a trusted employee of his new company, Karol fakes his own death and leaves his fortune to Dominique. When she comes to Warsaw for the funeral, he sneaks into her hotel room and, after the initial shock, they make love, finally consummating their relationship. However, in the morning, Dominique awakes to the police at her hotel room door, but Karol is gone and despite her pleading in French that he is alive, Dominique is arrested for Karol’s murder. At the end, we see Dominique signing to Karol through the window of the prison in which she is being held. She tells him that she still loves him and is willing to marry him again, if she can get out of prison. Karol begins to cry. He has succeeded in achieving equality with his ex-wife, but it is a bittersweet victory. This film is not uplifting like Blue or Red it is a dark comedic tragedy.

Then with the help of Mikolaj and a trusted employee of his new company, Karol fakes his own death and leaves his fortune to Dominique. When she comes to Warsaw for the funeral, he sneaks into her hotel room and, after the initial shock, they make love, finally consummating their relationship. However, in the morning, Dominique awakes to the police at her hotel room door, but Karol is gone and despite her pleading in French that he is alive, Dominique is arrested for Karol’s murder. At the end, we see Dominique signing to Karol through the window of the prison in which she is being held. She tells him that she still loves him and is willing to marry him again, if she can get out of prison. Karol begins to cry. He has succeeded in achieving equality with his ex-wife, but it is a bittersweet victory. This film is not uplifting like Blue or Red it is a dark comedic tragedy. If you remember in Blue, Julie is so absorbed in her own emotions that she doesn’t even notice the old woman and the recycling bin. But she also shows up in White while Karol is shivering on the streets of Paris. Karol notices her but only grins as she tries to put her bottle in the bin. I tend to think that Karol is happy to see someone to whom he finally feels equal. Finally, this is the odd man out of Kieslowski’s trilogy, because it is less artsy and more straight-forward it makes a good introductory film to get into Kieslowski’s work. But even though the ending seems like a hopeless tragedy, the true ending of White is actually revealed at the end of Red, where we see Karol and Dominique have reconciled and are re-married.

If you remember in Blue, Julie is so absorbed in her own emotions that she doesn’t even notice the old woman and the recycling bin. But she also shows up in White while Karol is shivering on the streets of Paris. Karol notices her but only grins as she tries to put her bottle in the bin. I tend to think that Karol is happy to see someone to whom he finally feels equal. Finally, this is the odd man out of Kieslowski’s trilogy, because it is less artsy and more straight-forward it makes a good introductory film to get into Kieslowski’s work. But even though the ending seems like a hopeless tragedy, the true ending of White is actually revealed at the end of Red, where we see Karol and Dominique have reconciled and are re-married.