Director Sam Mendes crafted an immersive World War I drama in 1917 through the clever use of practical camera tricks and special effects so we as the audience never leave the sides of our heroes. In fact, it is as if we don’t even blink. Roger Deakins starkly beautiful cinematography and an extremely talented editing team made it so that we never wanted to either.

The camera fixes its gaze on Lance Corporals Schofield and Blake through their rescue mission. It doesn’t cut from the action. It never leaves their side to show us an establishing shot or to tell us what is happening somewhere else. The entire film is one long and winding road through treacherous terrain.

If you’ve seen the trailer, you understand their mission. One of the soldiers’ brother is in a battalion miles away with another unit and they are going to charge into an ambush if they don’t hear from command. Armed with their message, they march off as a company of two bravely preparing to cross no man’s land and enemy lines in order to save 1,600 men including his brother.

From a Christian worldview, this mission rings of familiarity. We are called onto a mission that may cost us our lives. We are marching into enemy territory with a message that can rescue our brothers and sisters from the fire. The urgency and energy with which these soldiers carry out their mission should serve as a reminder to believers that the great commission is not completed. We must advance on our mission to bring this message of salvation to a world marked for destruction. They have been deceived and believe that victory is in their grasp.

Of course, in the film, the message is only good news because it means that this particular advance has been canceled. It would have been an even more powerful picture if the war was over and peace had been won. Then it would have truly been good news similar to the message that we as Christians proclaim. The enmity we have with God because of our sin ended through the sacrifice of the sinless Son of God, Jesus Christ.

Favorite Scene

There are a few short reprieves from all of the action. One of them comes after a particularly harrowing scene in which we follow George MacKay’s Lance Corporal Schofield through a terrifying ordeal only to see him emerge on the other side physically whole but mentally broken. He begins stumbling through a forest towards an ethereal voice. We’re not sure if this is part of the soundtrack or if he actually hears this angelic singing, until he stumbles into a camp of his fellow soldiers seated in the forest listening to an unnamed soldier sing…

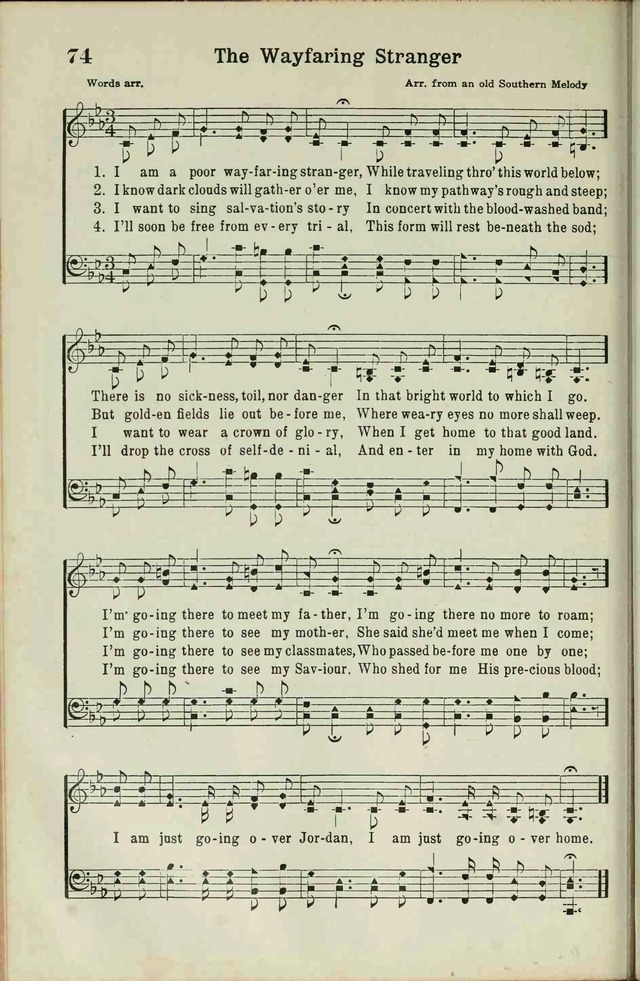

I’m just a poor wayfaring stranger

Traveling through this world of woe,

There is no sickness, toil, or danger

In that bright land to which I go.

I’m going there to see my Father.

I’m going there no more to roam.

I’m only going over Jordan,

I’m only going over home.

I had never had the pleasure of hearing Wayfaring Stranger in its heyday, but I’ve enjoyed listening to many different renditions since seeing the film. Its history stretches back to at least the time of the American Civil War when it was called Libby Prison Hymn, named for the Confederate prison that was in Richmond, Virginia.

Since its creation, it has a rich history both religious and secular. It appeared in the Broadman Baptist Hymnal in 1940 before Burl Ives popularized it in 1944. Later versions include Emmylou Harris in 1980, Johnny Cash in 2000, and, most recently, Jack White on the soundtrack of Cold Mountain in 2003.

This rendition is the most stylistically bare of all of those with no accompaniment, and just a solitary soloist, Jos Slovick, upon whom the cameras focus never rests. It could have been a throwaway scene transitioning from one massive set-piece to the next, but the camera methodically slows down and leaves our protagonist to show some of the other young men who are mentally preparing to face the horrors of war is profound. In that moment, the immersion into the setting has been completed. We are not just with them, we are one of them. Not soldiers, but just men, mortal men. Looking out across the river of our own mortality.

As believers, we are reminded by Paul in Philippians 4:13 that he “can do all things through Christ who gives me strength.” This is not a promise that all of our business ventures will succeed and that our sports teams will win. This is the Apostle Paul speaking as a man in prison nearing the end of his earthly life. He is getting ready to face death for the sake of Christ and he confesses that no matter whether he is hungry or full, sick or well, in bondage or free, he has learned the secret to contentment in all circumstances. It is not his best life now, it is Christ in him, the hope of glory.

This life is hard and we are not promised a delightful rose garden of a life. It is a war. We are called to live streamlined gospel-centered lives and when we reach our final moments we do not rest in the abundance of our possessions or the joy in the faces of our loved ones but in the hope of glory as we remember that to live is Christ and to die is gain.

Have you seen 1917? What did you think? Is it the best war film since Saving Private Ryan? If you haven’t seen it, it is extremely intimate and passionately created. It’s still in theaters and begs to be seen on the largest screen you can find.